Preview

Class Name and Date

Art 230: Ancient Art. Fall 2015

Format Type

Essay

Time Period

Classical Period

Theme

Gods and Goddesses in Early Classical Greece

Description

Greek Gods and Goddesses from the Early Classical Period

By Sabine Schmalbeck

The theme of this exhibition is Greek Gods and Goddesses from the Early Classical period. The Early Classical period, also called the Period of Transition, lasted from c. 480-450 BCE. [1] It was the transitional period between the Archaic period and the High Classical period.

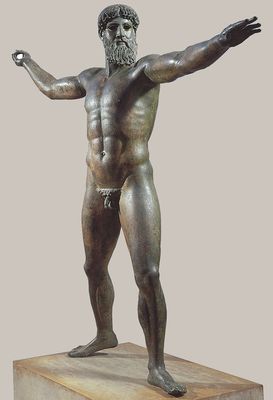

Throughout the Classical period, the Greeks were interested in humanism, rationalism, and idealism.[2] The attention to detail and realism are due to their dedication to depicting accurate human bodies. In the Early Classical period, the bodies, especially the sculpted pieces, show more realistic figures with the modeling of the anatomy. The pieces’ poses start to become more lifelike as the style moves away from the stiff, blocky characteristics of the Archaic period. An example of this is seen in the bronze statue of Artemision Zeus or Poseidon. The god’s pose is open and less rigid as the figure shifts his weight from his back leg to his front leg. An example of a popular way of portraying a more lifelike pose is seen in the Dionysus statue. The piece uses the relaxed, contrapposto pose.

The beginnings of contrapposto occurred in the Early Classical period.[3] As seen with Dionysus, contrapposto uses a weight-leg, free-leg stance. It conveys a more relaxed, lifelike pose. The torso of the side of the weight-bearing leg is shorter than the other side, and the shoulder of the shorter torso side is lower than the other. Many pieces of this period show the beginnings of contrapposto because while they have the weight supported on one leg, the shorter torso and the lower shoulder are on the wrong side, so it isn’t true contrapposto.[4]

Another characteristic of this period is the Severe Style; the Severe Style gets its name from the serious facial expression of the subjects.[5] The Severe Style portrays males with closely cropped hair, blank facial expressions, symmetrical and generic features, and a rounded, square chin.[6] The style conveys “simplicity, strength, vigor, rationality, self-discipline, and intelligence”.[7]

Artists during the Early Classical period used a variety of media from marble to ceramics to bronze to terracotta. The potters and painters continued to develop the red figure style popularized in the pervious period. Red figure painting is when the subjects are silhouetted in black paint leaving the red of the vessel unpainted to color the skin; the surface details are added in with additional black paint. Red figure allowed the artist to easily add more details, and the painters increased their ability to create “supple, rounded figures, posed in even more complicated and dynamic poses.”[8] The bronze sculptures were able to become more complex and larger due to the lost-wax process. The lost-wax process is when a wax sculpture is surrounded in a mold with a hole in the top and bottom. Metal is poured in the top and the excess material drains out the bottom leaving a hallow piece. Because it is hollow, the sculptures could be quite large without worrying about the heavy weight; it also made it easier to have outstretched limbs because it wouldn’t affect the balance as marble would.[9] The marble technique showed a more developed understanding of portraying anatomy with the modeling of the musculature instead of suggesting it with surface details.

The drapery in the Early Classical period is more lifelike than in previous periods. Instead of stylized patterns of the folds, the drapery falls in a way that more realistically shows the fabric gathering and the form of the body. An example of this is seen in the Terracotta statuette of Nike; the fabric is almost translucent as it presses against her legs while the folds of fabric between her legs and behind her body suggest movement. The cloth shows more observation by the artist instead of stylization. The depiction of drapery continues to develop in the following periods.

The Ancient Greeks believed in many gods; the main ones being the 12 Olympians. The gods and goddesses controlled many aspects of the Greeks lives. Because the gods had so much power over the humans, many temples and sanctuaries were built in their honor.

The temples and sanctuaries were places of worship; worship usually occurred at an altar outside near the temple. The actual temple was not a place for public worship; only a select few could enter the inner room that housed the cult statue of the god and the sacrificial implements.[10] The temple cella typically held the offerings and votive items that people gifted the deities; the treasury also held the offerings.

Some depictions of the gods and goddesses were simply a recreation of the deity while others showed scenes from the mythology. The Death of Aktaion krater, shows the story of Artemis setting Aktaion’s dogs on him after he saw her bathing. The mythological scenes often have a moral or a warning in them; this one reminded humans to respect the gods. Some artworks are for decoration or for as an offering to a deity. This one is a krater, which was most likely used as a “punch bowl” for wine.

A characteristic from the Early Classical period is generic, expressionless facial features. That means that the gods are usually identified by their iconography. For example, in the Mourning Athena relief, she is easily identified because she wears her helmet and her usual chiton garment. When there is no iconography, it becomes difficult to figure out who the subject is. With the Artemision Zeus or Poseidon the true identity is unknown. The subject is a god, and the identity was narrowed down between Zeus and Poseidon because of the beard, but without a lightning bolt or a trident, the identity can’t be more specific. While is can be difficult to differentiate between various deities, it is easier to separate the gods from the mortals. Gods and Goddesses aren’t depicted with their mouths open during this period; it is a physical symbol of their dignity and self-control.[11] Mortals usually have their mouths open to make them seem less poised as the deities.

The Early Classical period was a time of multiple technical advancements in various media. Many of the conventions and styles in this period remained and evolved in the following periods marking the Early Classical period as the beginning of the development of the iconic Classical Greek style.

Footnotes

1 John Griffiths Pedley, Greek Art and Archaeology, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2012), 207.

2 Marilyn Stokstad and Michael W. Cothren, Volume I Art History, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2014), 120.

3 Stokstad and Cothren, Volume I Art History, 120.

4 Sarah Archino, “ART 230: Early Classical Greek Lecture” (lecture at Furman University, Greenville, South Carolina, November, 6-11, 2015).

5 Pedley, Greek Art and Archaeology, 209.

6 Sarah Archino, “ART 230: Early Classical Greek Lecture”.

7 Andrew Stewart, “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning”, American Journal of Archeology 112 (2008): 602.

8 Stokstad and Cothren, Volume I Art History, 126.

9 Stokstad and Cothren, Volume I Art History, 120.

10 Robin Sowerby, Greeks: An Introduction to Their Culture (United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, 2014), 98-99.

11 Archino, “ART 230: Early Classical Greek Lecture”.

Works Cited

1. Archino, Sarah. “ART 230: Early Classical Greek Lecture.” Lecture at Furman

University, Greenville, SC, November, 6-11, 2015.

2. Pedley, John Griffiths. Greek Art and Archaeology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education Inc., 2012.

3. Sowerby, Robin. Greeks: An Introduction to Their Culture. United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, 2014.

4. Stewart, Andrew. The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning.” American Journal of Archeology 112 (2008): 602.

5. Stokstad, Marilyn and Michael W. Cothren. Volume I Art History. Upper Saddle

River: Pearson Education Inc., 2014.