Preview

Class Name and Date

Art 230: Ancient Art. Fall 2015

Format Type

Essay

Time Period

Classical Period

Theme

The Figure in High Classical Greek Sculpture

Description

The Male Figure in High Classical Greek Art: Striving for Perfection

By Jackson Goode

Ancient Greece is one of the most powerful civilizations to have ever existed, and despite being long gone, the impact of their societies are still felt even today. Over the course of a millennia, the peoples of the Peloponnese would evolve through many stages and give us the artistic ideals that still linger. The most significant of Ancient Greece’s artistic aspirations was their aim at true perfection.

Perfection is a lofty ideal, but in the art world, it is one that we run into frequently. Historically speaking, there has always been a “perfect” in regards to art—meaning a perfect function, place, imagery, etc. In Ancient Egypt, art was for the deceased for the express purpose of funerary rituals and religious beliefs, and because of this, Egyptian art does not come very close reality.[1] During the Renaissance, there was an interest in art being human.[2] The images strayed from the religious scenes that the Medieval period is known for, and naturalistic depictions of humans interacting with each other and with the world become the cornerstone. For the Ancient Greeks, though, the human body was perfect.[3] The human body is the perfect machine, and the Greeks had a deep respect for it. This is evident in the fact that the overwhelming majority of surviving Greek work is figurative. The Greeks expand on this, though. No one individual body is perfect, it is the relations of parts to the whole that are perfect.[4]

Ancient Greece also had a deep interest in mathematics. There were slight influences during the Archaic period by Babylonian society, but the Greeks interest in math stagnated until the Classical period.[5] The start of the Classical period of Ancient Greece is placed in the year 480 CE.[6] This year marked the defeat of the Persians at the Battle of Salamis. This decisive victory marked a turning point in the war. The previously divided city states could now band together, and it is at this time we see a joining of Athens and Sparta.[7] A year later, at the next decisive victory against the Persians at Plataea ended the Greeks worries of invasions, allowing civilization to blossom. This period is one of the high points of Greek civilization. Greece was absolutely flourishing. Athens came to organize one of the first alliances of many Greek city states, uniting them under the Delian League.[8] Members of this league were required to provide ships or money, and Athens became an imperial power. This wealth and prosperity served as a huge motivator for humanistic and artistic development, bringing in a style that was radically different than anything previous.

Before the Classical were the Geometric, Orientalizing, and Archaic periods. These periods are markedly different from the Classical, despite being separated by just a few centuries. The Geometric and Orientalizing periods were marked by their use of geometric shapes.[9] There was still an emphasis on people, but the people were not illusionistic at all. Heads were simplified into elliptical forms, the torsos broken down into triangles, and limbs became spindly cylinders. They were representational, but the emphasis on naturalism just wasn’t there. Archaic art is where we see the first sparks of naturalism in Greek art. The figures became more robust, more round, more real. The faces became less abstracted and strange and more grounded in life. There was a clear interest in “humanism, rationalism, and idealism,” which are noted as the driving forces of Classical Greek art, so it is logical that in a period of extravagance between the wars, a style such as the Classical would arise.[10]

This momentum continued on until the start of the Peloponnesian War that broke apart the Delian league in mid fifth century BCE.[11] Sparta came to dominate the Peloponnese, but Athens remained strong in its hold on the Aegean.[12] Continuing its imperial power, Pericles came to the forefront of Athenian politics, and with him came the start of modern democracy. A patron of the arts, Pericles helped usher in the High Classical period with his rebuilding of the Acropolis. The High Classical exists in a small, fifty year window in the fifth century BCE. This small window is seen as the pinnacle of artistic development, and it is denoted by many as the start of a true golden age.

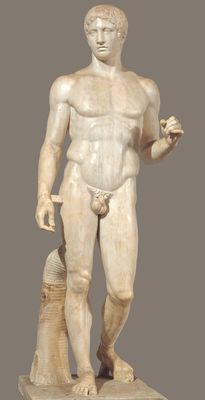

Marvelous works like Polyclitus’ Diadoumenos and Doryphoros exemplify this new style. They are more than perfect than perfection—more real than reality.. Every aspect of them is meticulously planned to be in perfect mathematical ratio to every other part.[13] Polyclitus did not call his sculpture the Doryphoros. Instead, he called his work Canon. It is a set of ideas to be followed to make another perfect form [14] The real question, though, is were the Greeks successful in their striving towards perfection.

Footnotes

1 Amy Calvert. “A beginner’s guide to ancient Egypt.” Accessed December 5, 2015 https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/egypt-art/beginners-guide-egypt/a/egyptian-art

2 Bruce Cole, The Renaissance Artist at Work: From Pisano to Titian, (New York: Harper & Row, 1983). http://arthistoryresources.net/renaissance-art-theory-2012/renaissance-artist.html

3 Beth Harris and Stephen Zucker. “Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer).” Khan Academy SmartHistory video, 5:07. August 11, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAR9RAMg9NY

4 Beth Harris and Stephen Zucker. “Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer).”

5 Luke Hodgkin, "Greeks and origins". A History of Mathematics: From Mesopotamia to Modernity. (London: Oxford University Press, 2005).

6 Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. "Art of Ancient Greece." In Art History. Fifth ed. (Pearson, 2013).

7 J. F. Lazenby, The Defense of Greece, 490-479 B.C. (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1993)

8 Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway. "The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tacg/hd_tacg.htm (January 2008)

9 Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. "Art of Ancient Greece."

10 Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. "Art of Ancient Greece."

11 Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. "Peloponnesian War", accessed December 07, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/event/Peloponnesian-War

12 Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. "Art of Ancient Greece."

13 Allen Farber. “Polyclitus’s Canon and the Idea of Symmetria.” SUNY Oneonta. Accessed December 5, 2015. https://www.oneonta.edu/faculty/farberas/arth/ARTH209/Doyphoros.html

14 Beth Harris and Stephen Zucker. "Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer)."

Bibliography

Calvert, Amy. “A beginner’s guide to ancient Egypt.” Accessed December 5, 2015 http://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/egypt-art/beginners-guide-egypt/a/egyptian-art

Cole, Bruce, The Renaissance Artist at Work: From Pisano to Titian, (New York: Harper & Row,

1983). http://arthistoryresources.net/renaissance-art-theory-2012/renaissance-artist.html

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. "Peloponnesian War", accessed December 07, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/event/Peloponnesian-War

Farber, Allen. “Polyclitus’s Canon and the Idea of Symmetria.” SUNY Oneonta. Accessed December 5, 2015. https://www.oneonta.edu/faculty/farberas/arth/ARTH209/Doyphoros.html

Harris, Beth and Stephen Zucker. “Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer).” Khan Academy SmartHistory video, 5:07. August 11, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAR9RAMg9NY

Hemingway, Colette, and Seán Hemingway. "The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.)".

In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tacg/hd_tacg.htm (January 2008)

Hodgkin, Luke, "Greeks and origins". A History of Mathematics: From Mesopotamia to

Modernity. (London: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Lazenby, J.F, The Defense of Greece, 490-479 B.C. (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1993) Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. "Art of Ancient Greece." In Art History. Fifth ed.

(Pearson, 2013).