Preview

Class Name and Date

Art 230: Ancient Art. Fall 2015

Format Type

Mosaic

Time Period

Hellenistic Period

Theme

Mosaics in Hellenistic Greece

Media

Tesserae

Dimensions

3.24 x 3.17 m

Description

In the transition to the Hellenistic Period, Greece was under the rule of the Macedonian leader, Alexander the Great. Artistically, he merged the two styles together to create a complimentary technique in designing the houses of the town, Pella, the capital of Macedonia. The heavily influential Greek style can be seen in the floor mosaics of the formal rooms in private houses and palaces in the area. A mosaic, which is created from tesserae (small cubes of colored stone or marble), provides a permanent waterproof surface ideal for floor decoration.[1] The most revered group of mosaics was mainly found in the “House of Dionysus” and the “House of the Abduction of Helen.” Their depictions belong to two categories: those with simply a geometric decoration covering the entire surface of the floor, and those with representative subjects, such as hunts, Amazonomachy (battle of Amazons) and others.[2]

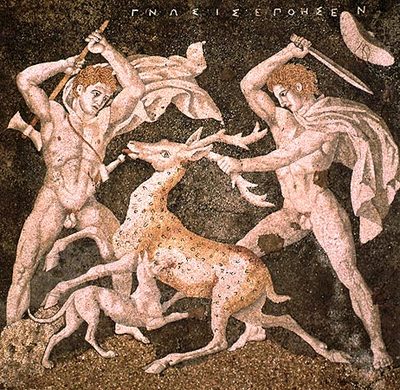

One of the most remarkable mosaics of animals and people in the House of the Abduction of Helen is the Stag Hunt Mosaic, prominently signed by an artist named Gnosis.[3] The blossoms, leaves, spiraling tendrils, and twisting, undulating stems that frame this scene are in a Pausian design. The coiling frame around it echoes the linear patterns formed by the figures of the hunters, the dog, and the struggling stag. The mosaicist has created an illusion of solid figures through modeling, mimicking the play of light on three-dimensional surfaces by highlights and shading.[4] Through this technique, the artist is able to reveal a sense of movement with the figures, creating a sense of illusion in the flat space. This is done by the deliberate use of the different color pebbles, creating that dynamism of shadow. Another expert approach to this illusion and the interpretation of action is the skill of foreshortening with the dog’s front legs as it sprints into the scene to attack the stag.

Although it is unclear at first glance, it is argued that the figure on the right is actually Alexander the Great, by virtue of the upswept hair off his forehead, as well as its central parting, dating it to the late 4th century. And although its credibility is limited, the taller figure is thought to be the god Hephaistos, due to his attribution of the double-headed axe, which the figure rears up to swing.[5] Because there is no identification of the figures by the artist, perhaps, according to Chugg, he is one of Alexander’s secretive and scandalous lovers.[6]

Regardless of the mosaic’s subject, the artistic skill in terms of shading and the illusion of shadow is exquisite and should be noted. In comparison to past mosaics, this work is all the more impressive because it was not made with uniformly cut marble in different colors, but with a carefully selected assortment of natural pebbles.[7] The movement of the figures is clear against the dark background, and their energy is definitely present as they hunt the surprised stag, succeeding in their mission of victory. The emotion of this scene makes it typical Hellenistic. The extreme violent movement of the nude figures and the intense drama of the hunt characterize this era’s unique stylizations.

Bibliography

Chugg, Andrew, Alexander’s Lovers. North Carolina: Lulus Publishing, 2006.

Stockstad, Marilyn and Cothren, Michael, Art History. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2014.

Ogden, Daniel, The Hellenistic World: New Perspectives. London: Classical Press of

Wales, 2002.

[1] Marilyn Stokstad and Michael W. Cothren, Art History (New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2014), 145-146.

[2] Daniel Ogden, The Hellenistic World: New Perspectives (London: Classical Press of Wales, 2002), 135-150.

[3] Stokstad and Cothren, Art History, 145-146.

[4] Stokstad and Cothren, Art History, 145-146.

[5] Andrew Chugg, Alexander’s Lovers (North Carolina: Lulu Publishing, 2006), 78.

[6] Chugg, Alexander’s Lovers, 78.

[7] Stokstad and Cothren, Art History, 145-146.